Recommerce Review: Hey Kong, thank you for joining us today. What’s your core idea at the moonbeam co. and how did it come about?

Qi Herng Kong: Hi! At the moonbeam co., we are all about fighting food waste by finding processing solutions to turn leftovers or byproducts from food production into new nutritional assets! My personal passion for this topic started when I was in the army. There I was in charge of supplies for my unit and I realized how much waste was generated in this kind of large-scale food service. It made me wonder how we could utilize all these resources since so much of it was being thrown away. I kept seeing the same issue at university. If you live on campus, especially in a residential college like I did, you notice that there’s a lot of food being thrown away.

I explored some ideas to tackle this food waste issue in student projects, but they were always on a small scale, and I couldn’t figure out how to operationalize it beyond charity or community-driven efforts. It was only in my third year when I met my co-founders that I started thinking about a social enterprise model – how to integrate environmental benefits into a business model that would allow for growth while also creating impact.

RR: So you started in school, that’s very interesting! What’s your academic background?

Kong: Yes, we started developing our idea during our studies but we directly went full-time last year, right after graduating. I actually studied pharmaceutical science at the National University of Singapore, followed by an innovation master’s at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore. But to be honest, all my internships and part-time jobs were in marketing. So, while my education was more technical, my work experience has always been marketing-focused and I have also taken on that role at Moonbeam.

RR: That’s interesting. Let’s take it from the top – you started out with rice beer as your first product, but it didn’t work out. Could you share more on that?

Kong: Yes, we initially started with making beer from rice, but soon hit some roadblocks. The main issue was that nobody really liked the taste of the beer. Additionally, our process caused a lot of the typical byproduct of brewing beer, called spent grains. These byproducts aren’t really used anywhere. In places like Germany, with their Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) programs, they have mechanisms to manage this waste. Typically, the spent grains are sent to farms for animal consumption, but Singapore doesn’t have many farms, and sending these byproducts to Malaysia also wasn’t an option. So, at first it ended up being incinerated, which destroyed valuable nutrients. We realized that the real opportunity was in repurposing these byproducts as food for people. Although we ultimately decided to not continue with the rice beer production, this is how we came up with our second product, granola that is largely made from these spent grains.

RR: Wow, that’s a very ingenious approach! So, you’ve pivoted a few times. Where does Moonbeam focus now?

Kong: After a few years of experimentation, we’ve refocused on coffee grounds. Coffee is something everyone can relate to. Just like spent grains, when we brew coffee, the fiber gets left behind. We now work with that fiber to create baked goods, which we sell back to the food service companies that initially provide us with the coffee grounds. It’s a full-circle approach, turning waste into something useful.

RR: Considering the innovativeness of your products and the different technical processes you guys tested, do you think these ideas could be monetized, perhaps by licensing the recipes or obtaining patents for the procedures? Or are there barriers to that in the food industry?

Kong: Food is a tricky space for patents. Unlike in engineering, where configurations are harder to copy, food can be replicated more easily. Even with tight intellectual property, someone can still figure out how to copy a product or process. Plus, from a financial perspective, as a startup, it’s not feasible to take on a big company in court over patent issues – it would cost more in legal fees than it’s worth. That said, we’ve been exploring licensing some of our recipes, like our coffee-ground-based sourdough. While we can’t patent it, licensing lets us scale and share our knowledge, even though others could eventually replicate it. But, once we license it, we face new questions about brand value and how to maintain our position in the market.

RR: Understandable concerns, but nonetheless an interesting option for the future. Coming back to your own products – Why are you focusing on the cookies and what does your distribution look like?

Kong: The cookies have taken the lead because they move faster, and we have a stronger B2B pipeline for them. Actually, at our core we are a B2B company, but our marketing sometimes makes it look like we’re B2C, especially since our outbound communication focuses a lot on consumer-facing channels. So while B2B is the priority, the B2C side helps us build brand awareness, and it’s useful for attracting potential B2B clients. We try to maintain a balance between the two.

RR: The focus on B2B sounds very interesting! Who are some of your customers?

Kong: Most of our sales are back to food services. For instance, our sourdough products are available at Google’s Singapore office. We also sell to the same operators who provide us with coffee grounds, so it’s a bit of a circular loop.

RR: So, focusing on B2B is a strategic decision. Do you see yourself growing in B2C as well, perhaps through retail partnerships?

Kong: Definitely. In a small market like Singapore, many food companies mix B2B and B2C because it helps them reach a broader audience. While B2B is our main focus, B2C can still play an important role in building brand presence. Pop-up events at sustainability and innovation fairs, for example, allow us to engage with both consumer and business audiences. They help establish our brand and connect with customers in a way that doesn’t depend entirely on B2B or B2C. From a financial perspective, B2C also helps with cash flow, as it’s a quicker turnaround compared to the longer sales cycles in B2B. So, we will eventually need both to create a strong and sustainable business.

RR: I see. And since your supply chain is tied to your distribution, how many sources of coffee grounds do you have right now? How challenging is it to collect all those ingredients?

Kong: Right now, we’re collecting coffee grounds from two sources, but we’re aiming to expand that to three. As we grow, the challenge becomes ensuring we have enough supply to meet demand. This is particularly important when we’re dealing with food processing facilities where supply and distribution are more interconnected. However, with other customers, like pantries, it doesn’t matter as much because we don’t always collect the coffee grounds directly from them. It’s all about how we help these businesses achieve their sustainability goals, which is where the B2B side really shines.

RR: So, in a way, your product can be seen as sustainability as a service for other companies?

Kong: Exactly. For larger companies, especially, we help them integrate more sustainable and circular practices into their operations. It’s about supporting them in meeting their sustainability KPIs.

RR: That makes a lot of sense. Do you track the impact of your products? For instance, do you measure how much waste you’re diverting or any environmental benefits?

Kong: Yes, we measure our impact on three levels: First, we track how much byproduct goes into our products. For example, our cookies are made with about 30% byproduct, meaning that for every 10 grams of cookie, 2 grams come from rice or other waste.

Then, we measure our environmental impact based on SDG goals. For instance, we track water use and carbon emissions throughout the lifecycle of our products. For our granola, we have even compared its impact to the emissions from incineration in Singapore.

Lastly, we also measure the social impact of our operations. We engage vulnerable communities – people with disabilities and youth at risk – in our manufacturing process. We track how many people we employ and the income they generate from working with us.

RR: That’s impressive. Speaking of your operations, do you manage your own production, or do you work with independent suppliers?

Kong: We manage our own facility, a 50-square-meter space in western Singapore. It’s small but effective. We employ some full-time staff that oversees production, quality control, and logistics. For tasks like packaging, we collaborate with the external groups mentioned, particularly those involving people with disabilities, and integrate them into our workflow.

RR: Does this setup give you the flexibility to scale up quickly if, say, a retailer like Fairprice approached you with a large order?

Kong: We could scale production if needed, but retail comes with its own challenges. Big retailers typically require upfront stock and have payment terms of up to 60 days, which strains cash flow for small businesses. There’s also the risk of overproducing and being left with unsold inventory. That’s why we focus on niche channels that allow us to grow sustainably without taking on the risks of retail.

RR: Very reasonable. As you have mentioned the financial aspect and given Singapore’s high operational costs, have you considered relocating production to another country?

Kong: Yes, we’ve discussed it. Singapore offers excellent infrastructure and regulatory support, but the high costs – like rent and labor – make scaling difficult. Expanding to a country with lower costs, such as Malaysia, could make sense if there’s strong domestic demand. However, Singapore’s strategic location and world-class ports are key advantages for exporting. Maintaining some local production could also help us retain certain brand benefits, especially for B2B markets and government procurement.

RR: How much are you producing currently, and who are your main customers?

Kong: We’re producing some thousands of bags and jars of cookies each month. It’s a solid output for now, though we could scale up if needed. Our customer base includes about 10 regular B2B clients, ranging from small specialty shops to larger partners. That said, with irregular orders, we’re serving closer to 20 customers in total at any given time. Some place frequent orders, while others come to us more sporadically.

RR: It sounds like you’ve found a strong rhythm. Would you say you’re financially in a good place right now?

Kong: Thank you! We’re technically profitable, but cash flow can still be tricky. The food industry operates on razor-thin margins, so turning a profit doesn’t always mean having a steady cash flow. For now, we’re focused on boosting revenue while keeping costs in check. Unlike tech startups, where scaling fast is the priority, we have to be mindful of costs right from the start in food manufacturing.

RR: I can imagine. Are you still also experimenting with new products?

Kong: Right now, the focus is on scaling our cookie production, especially since coffee grounds have become a key ingredient for us. But we’re experimenting with other products in the baking category. There’s a lot of potential there, and we see this as a category that can expand into different areas.

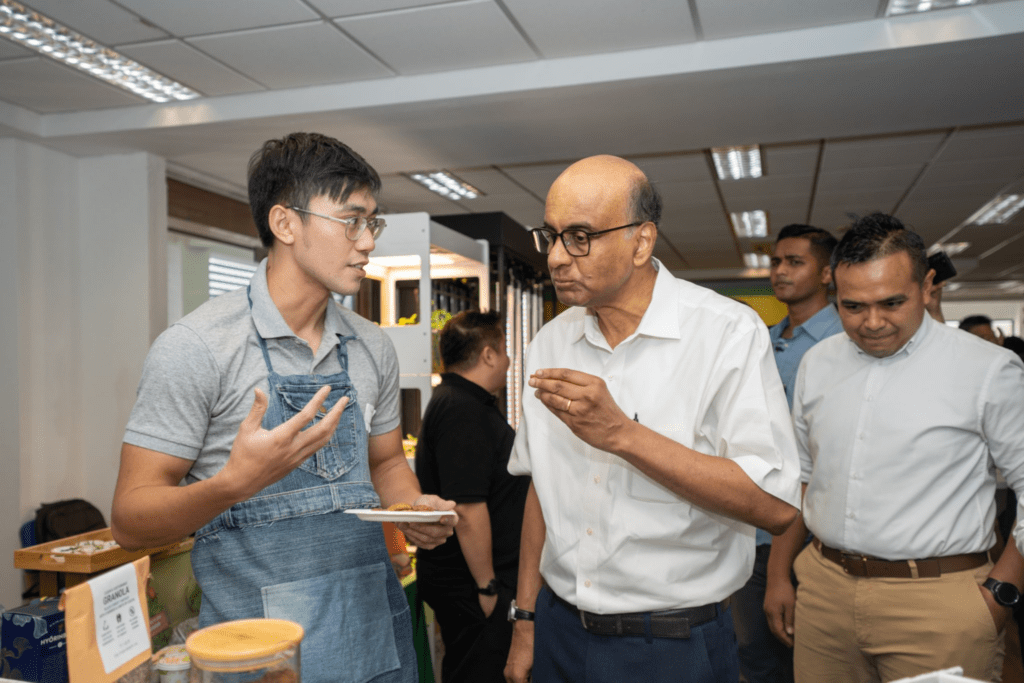

(Photo source: the moonbeam co.)

RR: Have customers been hesitant about eating products made from food waste? I noticed you have an extensive blog on your website, I assume that’s part of your strategy to educate people about the value of your products?

Kong: We’re lucky that here in Singapore, people are pretty open-minded about things like waste. Singaporeans have a long history of dealing with waste as a resource – like how we reclaim water – and that makes them less concerned about where food comes from as long as it’s safe. But, I have encountered some hesitation in foreign markets, where the perception is a bit different. People sometimes ask why they should eat something made from waste when perfectly good food is available. It’s a bit of a cultural barrier, but it’s not much of an issue in Singapore, thankfully.

And yes, the blog serves a couple of purposes. One is to educate people about how our products are made and why we choose to work with food waste. The other is marketing – because it helps spread the word and build a connection with our customers. It’s really important for us to explain our process and the impact of what we’re doing. Transparency is key, and it also helps make people more comfortable with the idea of consuming products that are made from food that would otherwise go to waste.

RR: Especially in the public eye, there’s sometimes an assumed conflict between being an impact startup and also being profit-driven. What is your opinion on this, and do you experience this sentiment from people in Singapore?

Kong: This conflict is something we encounter often. Many people still think doing good is limited to charities or governments, so a profit-driven business aiming for positive impact seems contradictory to them.

In Singapore, we see two main criticisms. First, suspicion – people ask, “What are you trying to exploit?” For example, because we work with people with disabilities, some assume we might be profiting off them. Second, confusion – many don’t understand why anyone would try to combine social impact with making money, as it doesn’t seem “business savvy” to them.

But in my view, this thinking misses the point. Both non-profits and for-profits need financial sustainability to achieve their goals. Businesses can create value efficiently, for society and consumers alike, and this value should be rewarded.

The challenge is that sustainability benefits can feel intangible. If someone eats a cookie made with two grams of food waste, they might wonder, “What difference does it make?” That’s why communicating impact and shifting mindsets takes time. But I believe the value we create deserves recognition and support.

RR: Do you see a trend towards more openness to the topic of impact entrepreneurship in Singapore?

Kong: I’d say that it’s still in its early stages, especially when compared to our neighboring countries. In developing countries, social enterprises are very well accepted, but in Singapore, we’re still figuring out what impact entrepreneurship should look like. The discussion on what businesses should do beyond just profit generation is definitely evolving. And simultaneously, for bigger multinationals, sustainability is becoming a major focus. So, what’s clear is that the conversation around sustainability and the role of business is becoming more prominent and that’s always a good sign for a positive development I would say.

RR: Since you mentioned MNCs focusing on sustainability, what would be your reaction if a large cookie manufacturer would also start offering cookies made from repurposed coffee grounds?

Kong: Honestly, that would be fantastic. I would love to see that kind of innovation happening across the industry. But I think it also raises an important question: Why have bigger manufacturers not been involved in these kinds of initiatives yet?

RR: Do you think it’s because of the added costs associated with sustainability?

Kong: Absolutely, that’s part of it. There’s often criticism about sustainable goods being more expensive. If you’re using recycled materials or food waste, why does the price still go up? The argument is that the cost of goods sold (COGS) should theoretically be lower. But there’s a flip side to that. The cost isn’t always in the raw materials – it’s often in the lack of economies of scale. The premium price for sustainably produced goods doesn’t just come from marketing; it also comes from the fact that it’s harder to achieve those economies of scale when you’re working with circular business models.

But yes, I think it would be great if larger companies embraced circular initiatives more openly. It could create valuable partnerships for smaller startups like ours. If a big company came in and offered to collaborate with us, it would solve a lot of challenges, like scaling production or gaining expertise. But as it stands, that’s not the reality. There’s resistance, but I believe with time, we can work through it and find ways to collaborate.

RR: Looking ahead, what’s your vision for the moonbeam co. over the next few years?

Kong: In a startup, you rarely think in terms of years, it’s more like planning for the next few months! But seriously, our goal is to scale while staying true to the triple bottom line. Every transaction should have meaning and impact.

We also want to inspire other businesses to follow suit, whether that’s by incorporating byproducts into their processes or adopting more inclusive hiring practices. We hope to show that it’s possible to hire beyond just the “perfect resumes” and create opportunities for those who’ve been overlooked.

Ultimately, it’s not just about growing our production capacity. It’s about creating a ripple effect – proving that sustainable, socially impactful businesses can make a real difference.

RR: Are you currently considering investors or partners to help scale those ambitions?

Kong: Not at the moment. Right now, our main focus is on building a solid client base. One thing we have already learned is that it’s better to start with paying customers, not investors. The funding landscape has slowed a lot recently, and for startups like ours, it’s crucial to get the top line in order first. Once you’ve got consistent revenue, investment opportunities tend to follow naturally. So for now, we’re prioritizing clients who align with our growth goals. Partnerships or capital injections might come later, but it’s not an immediate focus.

RR: Thanks so much for sharing your journey. We’re excited to see where you take things next!

Leave a comment